Researchers at Washington State University have teamed up with an amateur apple detective to bring fruit varieties thought extinct back to life.

A team with the Department of Horticulture joined apple sleuth David Benscoter to take cuttings at an abandoned orchard that has survived for 125 years on the slopes of Steptoe Butte, a 3,600-foot mountain on the Palouse.

Now, they’re grafting and growing those cuttings, preserving valuable traits so that some day consumers will bite into long-lost varieties once again.

Steptoe’s lost orchard

“The Palouse used to be the cradle for orchards,” said Amit Dhingra, an associate professor of horticulture. When irrigation arrived in the Columbia basin, the Palouse industry was decimated, but the trees survived.

A century later, people are exploring abandoned orchards and reviving lost apple types nationwide.

“Our food habits are changing,” said Dhingra. “Consumers are demanding more variety. These apples are a way to get variety and reclaim our heritage.”

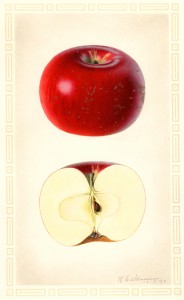

Last autumn, Benscoter, a WSU alumnus and retired law enforcement officer, sampled an apple from a tree at Steptoe Butte. Based on the taste, color, shape and core appearance, experts said the apple was the Nero, a variety grown across the United States a century ago but believed to be extinct at the time.

Robert Edward Burns, who homesteaded on the northeastshoulder of Steptoe in 1888, planted this Nero. He planted fruit trees where he couldn’t grow wheat.

Burns’ orchards stretch along ravines and slopes to catch any water that flows down the mountain. Their roots are shaded from the sun in Steptoe’s deep soil. While some of Burns’ trees are dead after more than a century, others are overgrown and scraggly but very much alive.

“The trees are still producing!” said Nathan Tarlyn, a research assistant in Dhingra’s laboratory who cut scions with Benscoter at Steptoe. “One hundred and twenty-five years, and they’re in good shape.”

Burns’ orchard days didn’t last long. Benscoter believes he planted too many apple varieties, instead of concentrating on the six most popular apples in the east, where most apples were shipped. By 1899, Burns lost the farm and soon moved away from the Palouse. But his fruit trees still remain at Steptoe, a living gene bank that preserves variety for future breeders.

“I find it incredible that Burn’s failure as a farmer may lead to one of the biggest finds of named lost varieties in one location,” Benscoter said.

Apple detective

Benscoter has a passion for tracking down apples. An amateur apple detective for the past seven years, he’s given talks across the state about varieties grown in Whitman County, 10 of which are still lost.

To find lost apples, Benscoter talks with Palouse residents and pores through old newspapers, plat maps, county fair records and family histories to learn what was planted, and who planted them. He compares that list with varieties thought to be lost or extinct. Then, it’s a matter of going to old orchards in the autumn and tasting the goods.

If he finds a lost-apple candidate, he sends it to identification experts based in Oregon. Using detailed descriptions written in the 19th and early 20th century, as well as old watercolor paintings, they check the flavor, shape and form of the apple, and inspect the structure of its core. If an apple fails in only one identification marker, it must be collected again the following year and sent to other experts across the United States.

Scions and spitters

From cold storage at the WSU Vogel Plant Biosciences building, Tarlyn carried out a tiny apple tree with bandaged branches, each hung with a silver tag and a name: Nero, Arkansas Beauty, Scarlet Cranberry and Fall Jeneting.

On a base of standard rootstock, Tarlyn attached four heirloom varieties— three discovered on Steptoe, one, Fall Jeneting, found in nearby Colfax, Wash. Two of the apples, Fall Jeneting and Nero, have been confirmed as rediscoveries. Arkansas Beauty and Scarlet Cranberry are considered possible rediscoveries and must undergo further analysis.“This is a bit of a Frankenstein,” said Tarlyn. “These are lost apple scions, grafted onto a host.”

Apple trees do not breed true. Apples can and do cross-pollinate, but out of hundreds of seedlings, only a handful will carry on desirable characteristics. Most feral seedlings are dubbed ‘spitter apples’ (“You take a bite, and spit ‘em out,” Tarlyn said.).

Breeders have long known that keeping desirable traits and making new apple varieties requires grafting.

“If a tree was any good, you gave it a name,” Tarlyn said. “If somebody liked that apple, you’d take cuttings, or scions, off it, and graft them onto other trees to get that apple back.”

He and undergraduate researcher Sonia Weatherly are using the Steptoe scions to propagate new plant material that they can use for grafts. Success means WSU will have a source of germplasm, or genetic materials, for rare varieties, and in a few years, someone may crunch a new Nero.

Reclaiming vanished varieties does more than bring back apples with unusual flavor or color. Lost apples could have valuable traits, such as disease resistance or drought tolerance, just waiting to be discovered.

“You don’t know what might be there that is of value, until you look at it further,” Tarlyn said. “But if you lose the heritage, it’s gone.”

Links to learn more

Read more about apple science and growing practices with these WSU Extension publications.

Visit the new WSU Tree Fruit website.

Read more about Robert Edward Burns and his Steptoe orchard.

Learn about Dr. Amit Dhingra‘s research at genomics.wsu.edu

Learn more about the WSU Department of Horticulture.

See more historic American apples at the online USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection.